A Brief History Of Raw Milk's Long Journey...

People have been drinking raw milk from animals for thousands of years. Really, the term "raw" is a misnomer because it implies that all milk should be cooked, but that's a topic for another page! Onward...

Whether it's from cows, goats, sheep, camels, yak, water buffalo, horses, donkeys or even reindeer, unheated, unprocessed milk has been a safe, reliable food source for a good, long time.

Even in the tropics, and centuries before refrigeration had been invented, raw milk was an important food source for many cultures. By exploiting the preservative benefits of fermentation, primitive peoples were able to take a great food and make it even better.

Having access to a nutrient-laden food from their animals gave many cultures a distinct advantage over their hunter-gatherer contemporaries (1).

Rather than having to go from kill to kill, with sometimes days in between, even nomadic tribes like the Maasai nearly always had a protein source at hand, whether it was milk, blood or meat (2).

With a readily available food supply at hand, members of societies were freed up to pursue more productive things like making babies, building permanent communities, conquering their neighbors and everything else that comes with not having to spend energy hunting for food.

Considering raw milk's role throughout history, it's simple to see that it's not a deadly food. If it were, all those dairy-loving primitive cultures would have died out long ago, leaving their vegetarian cousins to mind the store. At the very least, people would have dropped it from their diets entirely. And we haven't even gotten to germ theory yet...

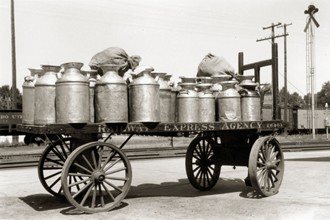

Closer to home, our early American ancestors lived in a farm-based economy. As the Industrial Revolution reached our shores, the cities swelled with job seekers lured from their farms by the factories and mills. By 1810, there were dozens of water-powered operations lining the rivers of southern New England, all staffed by thirsty workers.

With raw milk and whiskey being the main beverages of choice (hopefully not mixed!), demand for both grew along with the cities. When the War of 1812 broke out, the supply of distilled spirits from Europe essentially dried up. Although the conflict only lasted about two years, it's impact on our country was substantial, and strangely enough for milk, particularly nasty.

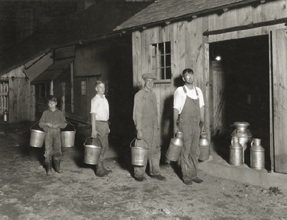

To meet the soaring demand for spirits, distilleries soon sprang up in most major cities. In one of the most bizarre twists of entrepreneurial insight, some brilliant soul thought it would be fun (and profitable) to confine cows adjacent to the distillery and feed them with the hot, reeking swill left over from the spirit-making process (3).

As you might guess, the effects of distillery dairy milk were abominable, and for many of those drinking it, amounted to a virtual death sentence. Confined to filthy, manure-filled pens, the unfortunate cows gave a pale, bluish milk so poor in quality, it couldn't even be used for making butter or cheese. Add sick workers with dirty hands, diseased animals and any number of contaminants in unsanitary milk pails and you had a recipe for disaster.

Lacking its usual ability to protect itself, and with a basic understanding of germs or microbes decades away, the easily contaminated "pseudo-milk" was fed to babies by their unwitting mothers. In New York City during 1870 alone, infant mortality rocketed to around 20% and stayed there for many more years (4).

The Distillery Dairy page mentioned above contains links to articles in the New York Times archives which enable you to 'read all about it' in the language of the era.

The situation languished for years until two men stepped up to the plate from different directions, united by a disaster common in the day- the death of a child.

In 1889, two years before the death of his son from contaminated milk, Newark, New Jersey doctor Henry Coit, MD urged the creation of a Medical Milk Commission to oversee or "certify" production of milk for cleanliness, finally getting one formed in 1893 (5).

By joining with select dairy experts, Coit (above, treating babies in New Jersey) and his team of physicians (unpaid for this work, by the way) were able to enlist dairy farmers willing to meet their strict standards of hygiene in the production of clean, certified milk.

After years of tireless effort, raw, unpasteurized milk was again safe and available for public consumption, but it cost up to four times the price of uncertified milk.

New York philanthropist Nathan Straus, who lost a child to milk contaminated with diphtheria, felt differently. He believed the only safe milk was that which had been pasteurized.

Straus (at right) made a fortune as co-owner of Macy's department stores and spent decades promoting pasteurization across America and Europe.

Using his considerable finances, he set up and subsidized the first of many "milk depots" in New York City to provide low-cost pasteurized milk (6).

While infant mortality did fall dramatically, other technological advances, such as chlorination of water supplies and reduction of previously ever-present horse manure (through the arrival of the automobile) occurred in the same time period making it difficult to say which change was most responsible.

Pasteurized and certified milks managed to peacefully co-exist for a time, but by the mid-1940's, the truce had become decidedly uneasy. In 1944. a concerted media smear campaign was launched with a series of completely bogus magazine articles designed to spark fear at the very thought of consuming raw milk (7).

Government officials and medical professionals, swayed by corporate dollars and lies, have effectively taken this valuable, healing food from the mouths of the people. Only in recent years has the consumer backlash against valueless processed foods grown to the point where access to clean, raw milk is once again being considered a dietary right.

References:

(1) http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2054675

(2) http://www.unpo.org/content/view/7920/125/

(3) http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/68/6/780?ck=nck

(4) http://www.tenement.org/Encyclopedia/diseases_marasmus.htm

(5) Milk, W.B. Saunders Co., 1921. Heineman, P.G., (pp. 482-510)

(Available on Google Book Search)

(6) http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?

res=9C00E3DA1630E033A25755C1A9639C94659ED7CF

(7) http://greenlivingjournal.com/page.php?p=1025